Small and mid-sized towns in Kansas and Missouri are seeing mass protests like never before

Across the U.S., people in small towns are mobilizing.

22 June 2020 | The Kansas City Beacon

A line of people join a march against police violence on June 7 in Hays, Kan., one of the small towns that has seen demonstrations since George Floyd’s killing. Courtesy photo: Nuchelle Chance

In Salina, Kan., protesters knelt for 8 minutes and 46 seconds — the amount of time George Floyd’s neck was pinned by a Minneapolis police officer.

In Maryville, Mo., demonstrations began with a prayer.

And in Pittsburg, Kan., more than 500 people gathered for a peace rally.

What do all of these places have in common? They all have fewer than 50,000 people — often much fewer.

Across the U.S., small towns are mobilizing in numbers that haven’t been seen before, protesting against police brutality and in support of the Black Lives Matter movement.

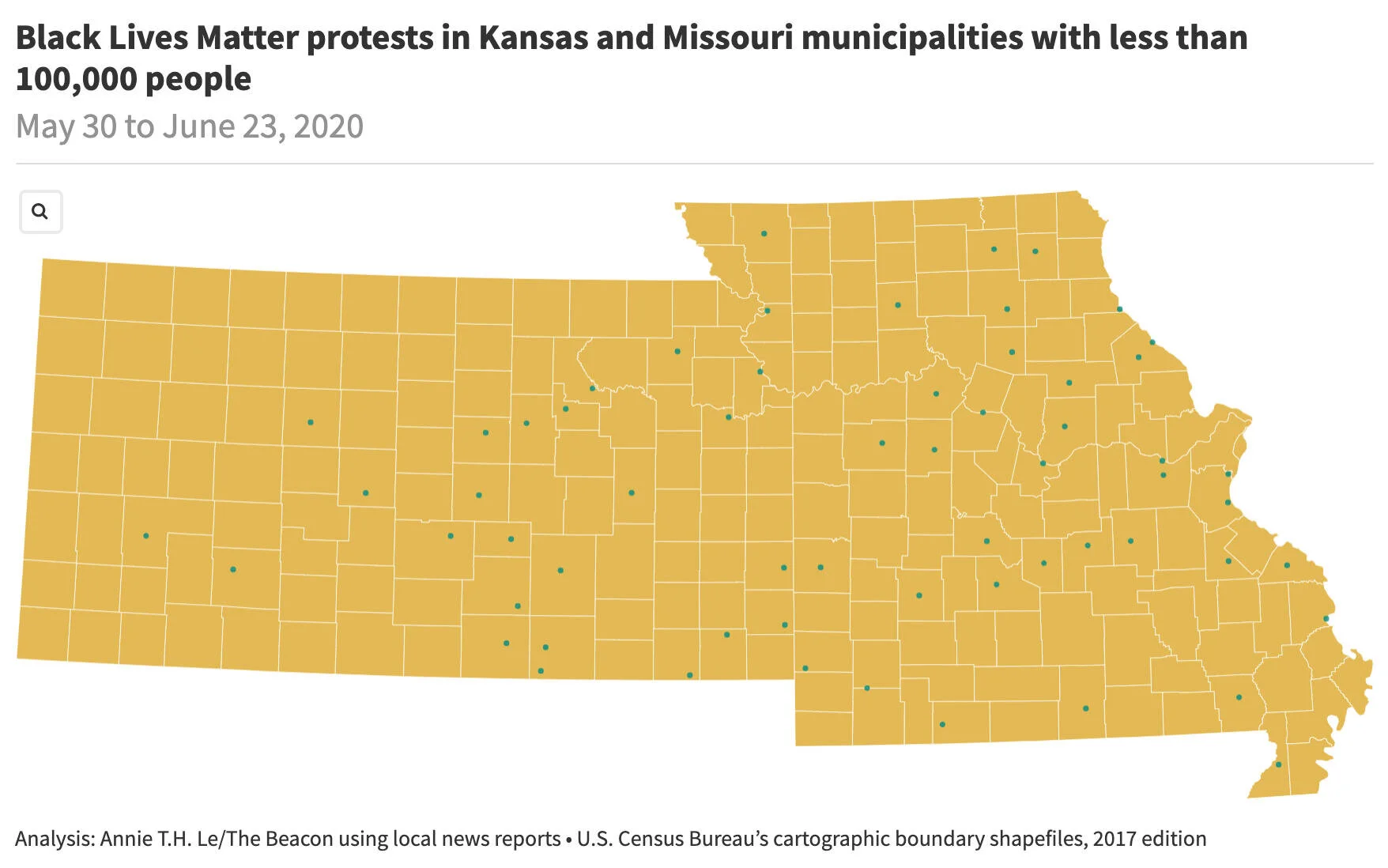

An analysis by The Beacon shows that more than 50 small and mid-sized towns across Kansas and Missouri have held protests since late May. The Beacon defined these as localities with a population under 100,000, excluding the suburbs of Kansas City and St. Louis, and focusing on areas that aren’t part typically part of larger metropolitans. Many of these areas tend to be predominately white with little to no history of protesting in recent years.

“It's unity across our country,” said Jess Piper, an activist in northwestern Missouri who recently attended a protest in Maryville, a town of 11,600. “We won't stand for the shooting of unarmed black people anymore … so it's really important for rural America to stand up.”

David Cunningham, a professor of sociology at Washington University in St. Louis, said these small-town protests are unique.

“I've been surprised to see the wide range of places and communities that have seen organized protests,” he said. “Certainly when we think of similar protests, campaigns in the past, they've been consigned more frequently to urban areas, more populated (and) more densely populated areas."

He said the issues related to the Black Lives Matter movement are not unique to just urban areas: police violence and structural and systemic racism occur in small towns. too.

“The size and scope of these protests are in part due to the fact that we are seeing a situation where racism has been expressed as a denial of humanity,” Cunningham said.

The lack of guidance from the federal level means people are taking politics into their own hands, Cunningham said.

‘WE NEEDED TO MAKE A CHANGE IN OUR TOWN’

Lucas Conner was born and raised in Nevada, Mo. — population around 8,200. The incoming high school senior had previously attended #MeToo and Black Lives Matter protests in Kansas City and Joplin, Mo. But on June 3, Conner organized a rally in his hometown.

“We can still have changes here in Nevada to make Nevada a better place for everyone,” Conner said.

Other organizers across Missouri and Kansas have varying degrees of experience with local activism. Nuchelle Chance, the adviser of the Black Student Union at Fort Hays State University in Hays, Kan., helped coordinate a protest in her town. Chance has always been involved in activism, whether it was helping out with voter registration or holding forums about civic engagement.

Gage Nunnery, 20, helped organize multiple protests in front of an old courthouse in Kennett, Mo., a town in the southeast bootheel of the state.

“We decided that we needed to make a change in our town before we worried about anyone else’s town,” Nunnery said. “There's a long history of racism and segregation and ignorance running through this town.”

In Garden City, Kan., demonstrations against police violence drew about 1,000 people on June 3. Courtesy photo: Carmen Robinson

‘WE WERE UNITED’

In Pittsburg, D’Andre Phillips Coble, president of the Black Student Association at Pittsburg State University, helped organize a peace rally at Immigrant Park, home to a memorial dedicated to the miners who worked around the area.

“Our objective was to get the people who didn't understand Black Lives Matter, the people who disagreed with it and the people who didn't acknowledge that this is a real issue within the world, to be at this peace rally because you need people to listen,” Phillips Coble said. “You need people to sit down and have those open and honest conversations.”

Phillips Coble had initially reached out to the Pittsburg Police Department and city for support and protection, which is different from most experiences protesters in larger cities have had. During the march, two police officers — both on bikes and dressed in business-casual uniforms — helped block off traffic to allow people to demonstrate.

“I didn’t want any type of police vehicles there because I didn’t want it to feel as if they're supervising us or they’re there to watch over us,” Phillips Coble said.

In Nevada, Conner and fellow demonstrators received threats of violence and words of intimidation from people in the community after he posted the Facebook event online. He, like Phillips Coble, then coordinated with the local police department.

“There were officers around,” Conner said. “And they were basically prepared to just protect us from anything coming.”

There were fears and rumors that outsiders — and in some cases white supremacy groups — would overtake the small-town protests, but that has yet to happen in Kansas and Missouri.

Many organizers from small towns said that they felt a unique energy during the demonstrations.

“We were united,” said Carmen Robinson, an incoming high school senior in Garden City, Kan., who helped organize a protest that brought together almost 1,000 people in her town.

“It was just so powerful,” she said. “I know the feeling, and I just can't explain it.”

Demetrius and Nuchelle Chance helped organize a protest in Hays, Kan., which drew over 200 people. Courtesy photo: Nuchelle Chance

‘MOST CHANGE DOESN’T HAPPEN ON THE MACRO SCALE’

In political science, the cycle of contention is the idea that for a period of time, protests will gain momentum until inevitable decline. There is a higher chance of political change during the height of a movement’s momentum.

“The most difficult thing for organizers is to figure out how to extend that window and increase protests so a campaign lasts longer and exerts more pressure on authorities and gains more from that work,” said Cunningham, professor of sociology at Washington University.

Ultimately, how organizers plan to mobilize and act now will determine how long they can keep people interested in the movement in their communities, he said.

“It’s really important for rural America to stand up.”

George Weddington, a PhD candidate at the department of sociology at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania, has studied grassroot organizing in social and race movements like Black Lives Matter for six years. He said organizers need to develop and understand their strategies and goals to sustain the energy behind current protests. He said one strategy is to create a movement organization that can exist over time and continue the work.

“A lot of times, we think about how organizers make protests when a lot of times the inverse occurs,” Weddington said. “I would say that protests make organizers. You have a bunch of people that will put together a protest, and then have a bunch of people who are energized and wanting to continue to work and they don't really have a plan.”

While it is difficult to holistically understand and predict the long-term impact of small-town protests right now, community members are continuing to address social issues in their towns.

In Pittsburg, Phillips Coble plans to bridge the gap between the local police department and the community when school is back in session. Meanwhile, Nunnery wants to establish a Black Lives Matter chapter in Kennett.

“Most change doesn’t happen on the macro scale,” Nuchelle Chance said. “If you expect change that you’re working on to happen overnight, you’re probably not working and fighting for something big enough.”